If you’ve ever asked yourself, “How much conservative money should I have? Should my portfolio be 60/40? Should I live off dividend income? What about Roth conversions?”—you’re not alone. Those questions often float around in the circles of people who’ve crossed the threshold of wealth and worry: “Now what?”

Today, Ari and I are going to walk through a case study of a couple with a net worth north of $10 million. We’ll show you how we think about spending, investing, tax strategy, and legacy—especially in that zone where you’re asking, “How do I make this money really matter?”

The Big Questions Everyone Asks

Before we dig into the numbers, here’s what usually comes up for folks in this seat:

- How much should I hold in conservative assets versus growth assets (e.g. a 60/40 portfolio)?

- Should I load up on dividend-paying stocks so I can live solely off dividend cash flow?

- Are Roth conversions worth doing at my level—especially when other wealthy people in my circles talk about them nonstop?

- If I inherited a lot (or sold a business), how do I use that capital to support children, grandchildren, causes — and pass it on efficiently?

- Do I need a basic trust or something more complex (e.g. dynasty trusts, charitable vehicles) given my balance sheet?

- What tax strategies become critical once you cross ~$10 million, and how are they different when you’re “just” in the millions?

To bring this alive, Ari and I are going to run through a sample case. You’ll see how the assumptions shift everything — and how the questions above begin to clear up.

Meet the Case Study Couple: $14M Net Worth

Here’s the framework we’ll use:

- Spouse A has $2.4 million in 401(k)

- Spouse B has $2.2 million in a taxable/invested bucket + $250,000 in Roth IRA + $50,000 in HSA

- Plus—and this is crucial—inherited stock (the “lucky sperm-and-egg club” money) of $8.5 million, in two concentrated positions (Apple and Amazon)

So total net worth: about $14 million. (Replace “inheritance” with “business sale” or “liquidated real estate”—the dynamics are analogous.)

They ask: How much can we spend now, safely? And then, how do we layer in investment, tax, and estate strategies to preserve optionality, reduce regrets, and leave a legacy?

Step 1: How Much “Too Much” Is Passing Away With

One of the first conversations we have is: Is it even possible to pass away with “too much” capital? In this case, projections suggest they could be on track to finish with ~$70 million if things go their way.

But let’s pause and reflect: what would you regret? Would you wake up at 85 and say, “I wish I’d taken more trips, given more, enjoyed more when I had energy”? If so, you don’t want your plan to err excessively on frugality.

So the first step is: determine a baseline comfortable spending level—something that feels sustainable—and then stress-test upward from there. In this case, we explored $25,000/month (i.e. ~$300,000/year) of inflated-adjusted spending.

Then we modeled $50,000/month ($600,000/year after taxes). Big difference. That swing leads to ~$33 million less in terminal wealth. These are not trivial margins at these asset levels.

Step 2: The Power and Risk of Your Investment Mix

The difference between “conservative” and “moderate-to-growth” allocations is huge at this level. In one scenario, we shifted the couple to a “preservation” posture.

The result: they risked running out of money by age 75. Even though they have millions, the assumptions matter deeply: return rate, inflation, sequence-of-returns risk.

That’s where the “fun” of financial planning meets the rigor. You can’t assume linear growth forever. You must ask, what happens if you underperform? What if inflation surprises you? What if taxes change? You need to stress-test. And you need optionality—enough liquid, flexible capital to lean on if markets disappoint.

Remember: wealth at this scale doesn’t immunize you. A “safe” portfolio here still needs guardrails.

Step 3: Design Your Spending & Lifestyle Envelope

Here’s a practical thought experiment: Suppose this couple wants to travel luxuriously, first-class, with family and friends, beginning in their early retirement years. Let’s say $150,000/year for those trips over a 30-year span (so from 55 to 85).

That’s a heavy lift. Over time, it’s ~ $11 million less in terminal wealth. But they’re still in a comfortable place.

The lesson? You can layer in “extras,” but you should model them explicitly. You don’t want to be surprised three decades in, asking, “Why does it feel like I can’t afford anything?” or worse—regretting opportunities you skipped.

One framework I like: identify a core spending level (what you need for quality of life) plus an extras budget (travel, experiences, giving). Model both. Know where the boundary is where extras begin to bite into your legacy.

Step 4: The Big Levers

Now, back to those questions you probably had in your head while reading:

How much conservative money should I have / should I do 60/40?

There’s no zero-risk portfolio. Even bonds carry duration and interest rate risks. At $10M+, you likely want a base of capital that’s “more stable” (credit, high-grade bonds, cash) but not so much that your growth potential vanishes. As your base, you might hold enough “liquidity + bond buffer” to weather downturns for several years. The rest can stay in growth and alternative allocations.

A strict 60/40 is a starting point, not a gospel. At this scale, you’ll want dynamic adjustments, tail hedges, opportunistic allocations, tactical tilt, and liquidity buffers.

Should I just invest in dividend stocks and live off dividends?

In theory, that sounds appealing — “set it and forget it, live on cash flow.” In practice, dividend yields compress, taxes bite, and growth is sacrificed. Dividend-only strategies may be too inflexible. You might want a hybrid: growth+dividend plus yield vehicles (real assets, preferreds, core infrastructure).

The point is flexibility. Don’t fence yourself in.

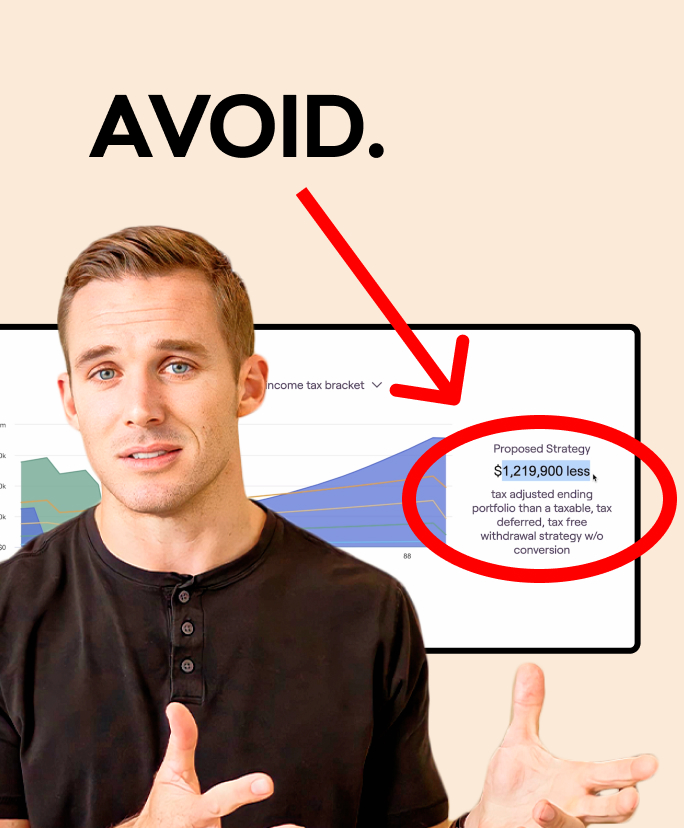

What about Roth conversions?

Yes — Roth conversions become a powerful lever. When your taxable rate is favorable versus expected future rates, converting portions while you have “room” gives you greater tax flexibility down the road. And when you’re in the higher-net-worth zone, managing when taxable income lands becomes critical.

Conversions must be case-by-case. Watch your AGI rules, phaseouts, and legislative risk.

What estate / trust structures do I need?

A “basic trust” might suffice when you’re under a certain threshold. But once you’re in the $10–30M+ range, more advanced tools (dynasty trusts, grantor trusts, charitable remainder trusts, pooling trusts) often make sense. You’re optimizing for flexibility, tax efficiency, control, and generational fairness.

Which tax strategies matter most?

At this level, a few things shift into primary importance:

- Timing income and realizing gains strategically

- Roth conversions (and undoing in bad markets)

- Harvesting losses / tax-gain spacing

- Bundling gifts / GRATs / IDGTs (for family transfers)

- Charitable vehicles (CLTs, CRTs, donor-advised funds)

- State tax domicile planning

Compared to someone with, say, $2–5 million, your margins are thicker, your planning windows are longer, and the legislative risk is greater. So constant vigilance and flexibility matter.

Step 5: Stress-Test, Recalibrate, Repeat

Every projection is an assumption. You’ll want sensitivity analysis: what if equity returns are 2–3% lower? What if inflation runs hot? What if markets snag you early in retirement? What if a concentrated stock position implodes? What happens if tax policy changes?

The goal is not perfect. The goal is resilience. Your plan should give you optionality. It should let you lean in or pull back depending on how things unfold.

You also want regular recalibration. What your plan assumed at 55 will change by 65. Make sure you revisit, rebaseline, and adapt.

The Bigger Picture: Don’t Just Accumulate, Use the Wealth

Ultimately, money is a tool. At this level, your biggest risks are not investment returns, they’re regret and missed opportunity. As you’ll see, a person with tens of millions can still fear running out or feel constrained, especially if they never defined what this capital is for.

To me, wealth is a lens on possibilities—giving, impact, family support, adventure, creative purpose. Use your plan not just to preserve but to live. Dream. Act. Be generous. But do so with eyes open.

Final Thoughts & Next Steps

We’ve walked through a high-level illustration of what life looks like with $10–20 million in net worth. We’ve explored how assumptions shift outcomes, how even small changes in spending or allocation cascade into large effects years out, and how the big levers (tax strategy, estate design, asset allocation) differ in this zone.

In upcoming content, Ari and I will go deeper into the nuts and bolts: trust structures, Roth conversion bands, concentrated stock management, giving strategies, liability protections, edge-case tax planning, and more.

If you’re in this situation—or approaching it—and want a thoughtful partner who lives these tradeoffs daily, reach out to us at Root.

The information presented is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as personalized investment, financial, tax, or legal advice. The content discusses general wealth management strategies and is not intended to recommend any specific course of action for any individual.

This article discusses a real client case with identifying details removed to protect privacy. It reflects that individual’s specific circumstances at a given point in time and should not be interpreted as a general recommendation. Financial strategies should always be evaluated in light of your unique goals, risk tolerance, and financial situation.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. All investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal. Any forward-looking statements or projections are based on assumptions that may not hold true in all market environments. Actual outcomes may differ significantly.

Root Financial Partners, LLC provides tax planning as part of its financial planning services. However, we do not prepare tax returns, represent clients before the IRS, or provide legal advice. Clients should consult their CPA, tax professional, or attorney before implementing any tax or legal strategies discussed.

Financial, tax, and estate planning strategies mentioned—including Roth conversions, gifting strategies, asset allocation decisions, and trust structures—are general in nature. Their suitability depends on your specific income, net worth, estate planning needs, and long-term objectives.