If you’re aiming to retire early, you probably keep hearing the same three tax strategies on repeat:

- “Should I lower my income to qualify for a health insurance subsidy?”

- “Should I convert part of my 401(k)/IRA to a Roth while my tax bracket is low?”

- “Should I harvest long-term capital gains at a 0% federal tax rate if I can?”

Each of those can be powerful. The hard part isn’t knowing what exists—it’s knowing what to prioritize for your situation and when to do it.

Below, Ari and I outline a simple way to think about these levers, then walk through a case study to illustrate how we determine which lever is “good,” which is “better,” and which is “best” for a given household. I’ll finish with practical rules of thumb for portfolios ranging from six figures to eight figures.

The “Tax Window” Most Early Retirees Overlook

Picture a typical timeline:

- Age 55–60: Still working, earning a healthy income.

- Age 60–early 70s: Retired with lower taxable income. This is your tax window—a period where you control how much income shows up on your return.

- Age 73–75+ (depending on your birth year): Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) begin from pre-tax accounts, pushing taxable income back up—often more than people expect.

That middle stretch—after paychecks stop but before RMDs (and sometimes before Social Security)—is where careful planning can permanently lower lifetime taxes. That’s where the three levers come in.

The Three Big Levers (and What They Actually Do)

1) Health Insurance Subsidies (Pre-Medicare)

If you retire before Medicare, the Affordable Care Act may subsidize part of your premiums when your taxable income stays below certain thresholds. Keeping income intentionally low for a few years can be worth tens of thousands of dollars—sometimes more once you account for compounding, because money not withdrawn to pay premiums can keep growing in your portfolio.

Key idea: Every dollar of income you don’t realize might help preserve a subsidy. The tradeoff is that the income you “skip” today is income you may need to recognize later (via RMDs, Roth conversions you didn’t do, or portfolio withdrawals).

2) Roth Conversions (Pre-RMD)

Moving dollars from a pre-tax IRA/401(k) to a Roth IRA means you voluntarily pay tax now to avoid potentially higher tax later—and you remove those converted dollars from future RMDs. The value of a conversion depends on two things:

- Your current marginal tax rate, and

- Your future expected marginal tax rate (including the effect of RMDs, Social Security, pensions, dividends/interest, and potential tax law changes).

Sometimes conversions save a fortune. Other times they’re neutral—or even harmful. Modeling the full retirement income picture helps you see which it is for you.

3) Tax-Gain Harvesting (in Taxable Accounts)

If your taxable income is low enough, some or all of your long-term capital gains can be realized at 0% federal tax. Harvesting gains at 0% raises your cost basis, which can reduce future taxes when you eventually sell those shares. It can also be used to rebalance without triggering tax you’d otherwise pay.

Important: This is different from tax-loss harvesting. Here, you’re taking gains on purpose during low-income years to reset basis.

Case Study: John & Jane

Let’s meet a hypothetical couple, John (55) and Jane (49), with a 21-year-old son. They’ve saved diligently and built a sizable nest egg. (Your numbers will be different, but the framework carries over.)

Their balance sheet looks like this:

- Traditional 401(k)/IRA: $1.2M

- Roth IRA: $161k

- Taxable brokerage (“superhero” account): $5.6M

- Cost basis (what they invested over time): $1.7M

- Unrealized gains: $3.9M

They plan to retire at 60, spend around $15,000/month, travel some, and maintain flexibility. The question isn’t “Which strategy exists?” It’s “Which strategy matters most for them, and in what order?”

What We Analyze First

I always start by modeling Roth conversions across time because it creates a baseline for comparison:

- Project expected taxable income each year of retirement (Social Security timing, dividends/interest, pensions, part-time work, rental income, etc.).

- Layer in current tax brackets and known changes (keeping in mind laws sunset or change).

- Estimate future RMDs if no conversions are done.

- Test various conversion amounts and brackets.

This baseline tells us if conversions are a big win, a minor win, neutral, or a loss. Then we compare that result to:

- The present value of likely health insurance subsidy savings before Medicare, and

- The benefit of tax-gain harvesting (how much gain we can realize at 0% federal, how much it helps diversification/rebalancing, and how much future tax we avoid by stepping up basis today).

Why Order Matters

You can’t fully maximize all three at once. For example:

- Filling lower tax brackets with Roth conversions raises income and could reduce or eliminate a health subsidy.

- Harvesting gains raises income too (capital gains are income for subsidy calculations), potentially affecting both subsidies and your ability to convert at low rates.

- Preserving subsidies by keeping income low may mean fewer conversions and less gain harvesting now—by design.

So we rank them.

When “Do Nothing” Is the Smartest Move

Not every year requires a move. If modeling shows Roth conversions don’t create a meaningful lifetime benefit—or actually increase lifetime taxes—then the best strategy is to intentionally do nothing for that lever in that year. The same is true for gain harvesting if you’re already at a subsidy cliff or near a bracket you don’t want to cross.

A disciplined plan often alternates priorities by year: preserve the subsidy one year, then harvest gains or convert the next, depending on market returns, spending, and how close you are to RMD age.

Rules of Thumb by Portfolio Mix (Not by Portfolio Size)

You’ll hear me repeat this: it’s not just the size of your portfolio—it’s the composition.

- Heavier in pre-tax (IRA/401k): I’ll lean toward Roth conversions during the tax window so RMDs don’t push you into higher future brackets.

- Heavier in taxable with large embedded gains: I’ll lean toward tax-gain harvesting—especially if a few positions dominate your risk. 0%-rate harvesting can help diversify without handing Uncle Sam a big check.

- Smaller overall portfolio or tight spending margin: I’ll often lean toward preserving health insurance subsidies first. In some cases, the real-world value of those savings (and the compounding from not withdrawing to cover premiums) outweighs modest conversion or gain-harvest benefits.

A Quick Spectrum

- Around $100k total and modest pre-tax balances: Subsidy planning typically matters more than conversions or gain harvesting.

- Mid-seven figures with large pre-tax balances: Conversions often move to the front of the line—if the modeled savings are meaningful.

- High-net-worth with big taxable gains and concentration risk: 0% tax-gain harvesting (paired with thoughtful rebalancing) can be the star of the show, while conversions are calibrated to avoid tripping undesirable brackets or IRMAA surcharges later.

(IRMAA = potential additional Medicare premiums tied to income. Another reason the sequencing of income matters—both before and after Medicare.)

How 0% Tax-Gain Harvesting Works (Tactically)

Suppose you own a large position in a stock or fund with significant appreciation. During a low-income year:

- Determine the room you have before crossing out of the 0% long-term capital gains bracket at the federal level (remember, state rules may differ).

- Sell enough shares to realize gains up to—but not beyond—that room. (You’re not selling $50,000 of value; you’re realizing $50,000 of gains. Cost basis matters.)

- If you still want the position, you can repurchase it right away—no “wash sale” rule applies to gains—effectively resetting your cost basis higher at little to no federal tax.

- If your bigger goal is diversification or rebalancing, you can instead direct the proceeds into the positions you’re underweight, staying within your 0% room.

Do this methodically over a few low-income years, and you can meaningfully reduce the embedded tax burden of your taxable account—and end up with a portfolio that matches your risk plan.

When Spending Changes the Answer

Here’s a twist we see often: a change in your spending can flip the “best” answer.

In our case study, simply doubling the couple’s planned spending reduced the modeled value of Roth conversions dramatically. Why? Higher ongoing withdrawals left fewer future dollars subject to high-bracket RMDs, changing the conversion math. In that version of the plan, tax-gain harvesting and portfolio diversification rose in importance, and “do fewer or no conversions” became the better call.

The lesson: Don’t decide your tax strategy in a vacuum. Update the plan when your spending, market returns, or income sources change.

A Simple, Repeatable Prioritization Process

- Model Roth conversions first. Quantify the lifetime value (or cost) across realistic scenarios of Social Security timing, market returns, and spending. This becomes your benchmark.

- Quantify subsidy value. Estimate the dollar savings of staying under the relevant ACA thresholds until Medicare, and consider the compounding benefit of not withdrawing those dollars.

- Assess tax-gain harvesting. How much can you harvest at 0%? How does that help diversification and future tax?

- Rank them for this year (and the next 1–3 years), knowing you can’t maximize all three simultaneously.

- Re-run annually. Markets move, brackets change, and your life evolves.

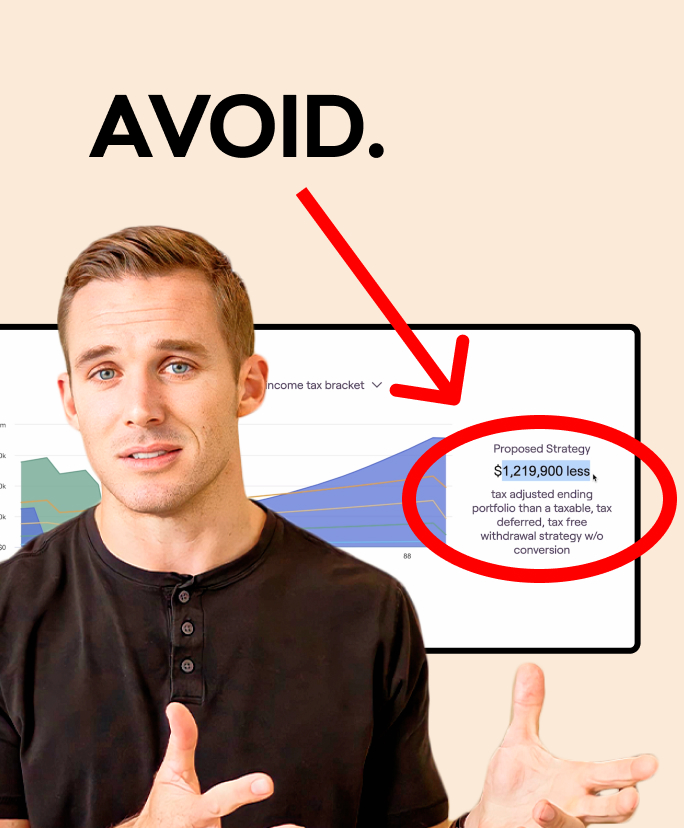

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Chasing a strategy because it’s trendy. Roth conversions aren’t automatically good. Neither is gain harvesting. Do the math.

- Ignoring the subsidy cliff. Realizing a little too much income can cost far more in lost subsidies than you gain from a conversion or harvest.

- Letting a single stock dominate risk. If big embedded gains are the only reason you’re concentrated, 0% harvesting during low-income years is a gift—use it to diversify thoughtfully.

- Forgetting about RMDs and IRMAA. Your 60s decisions can lower (or raise) what you’ll pay in your 70s and 80s.

The Sign of a Good Plan

At Root, our job is to line up the tax levers with the life you actually want: when you retire, what you spend, how you invest, and how much flexibility matters to you. The sign of a good financial plan isn’t a clever tax move—it’s a life well-lived with fewer unpleasant surprises from the IRS.

If you want a second set of eyes on your plan—tax, investments, withdrawal strategy, estate, and insurance—we’re happy to help.

This article is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as personalized investment, tax, or legal advice. It discusses general early-retirement tax concepts—such as ACA health-insurance subsidies, Roth conversions, tax-gain harvesting, RMDs, and Social Security/Medicare considerations—and is not a recommendation to take any specific action.

Tax and benefit rules change. Brackets, thresholds (including ACA subsidy eligibility, capital-gains bands, IRMAA surcharges), RMD ages, and deductions are subject to revision and can vary by state. Your filing status, other income, deductions, and residency may materially change outcomes. Always verify current rules and consult qualified professionals before acting.

Hypothetical case study. “John and Jane” are illustrative only and do not reflect any specific client. Projections and scenario analyses are estimates and not guarantees of future results.

Investing involves risk. Past performance is not indicative of future results. All investments can lose value, including loss of principal. Diversification and asset allocation do not ensure a profit or protect against loss.

Not tax or legal advice. Root Financial Partners, LLC (“Root Financial”) provides tax planning as part of its financial-planning services; we do not provide tax preparation services, represent clients before the IRS, or offer legal advice. Ideas discussed here—including but not limited to Roth conversions (including backdoor strategies), tax-gain or tax-loss harvesting, ACA subsidy planning, charitable strategies, estate-planning tactics, Social Security claiming strategies, and withdrawal sequencing—can trigger tax consequences or legal implications. Consult your CPA and/or attorney to evaluate suitability and compliance for your circumstances.

Suitability depends on your full picture. The appropriateness of any strategy depends on your income, age, health-insurance status, account types and cost basis, risk tolerance, time horizon, estate plan, and other factors. Nothing herein should be interpreted as a recommendation to adopt a particular tax position, make a specific investment, or change coverage.

Root Financial Partners, LLC is an investment adviser registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. For additional information, please review our Form ADV and firm disclosures available upon request.