Most people don’t realize this, but retiring later in life changes the rules. You have fewer go-go years, less runway for recovery, and required minimum distributions are right around the corner. But at the same time, you also have more clarity than many early retirees ever will.

When you retire after age 65, the decisions you make matter more, and they are different than the decisions faced by someone who retires at 55 or even 62. This isn’t about playing defense or simply being conservative. It’s about designing a strategy that aligns with your health, your energy, your purpose, and making sure the math actually supports the life you want to live.

What follows are the key areas people retiring after 65 need to get right, because these things work differently later in life.

Why Standard Withdrawal Rate Logic Breaks Down

One of the first things that changes when you retire later is how you should think about withdrawal rates. Most traditional retirement guidance assumes a 30- to 40-year retirement.

The 4% rule, guardrails strategies, and many Monte Carlo-based assumptions are built on the idea that your portfolio needs to last for several decades. If you are retiring after 65, that assumption often no longer applies.

If you retire at 70, for example, you may be planning for a 20-year retirement, not 30 or 40. When you apply a traditional 4% withdrawal rate to a 20-year time horizon, there’s a strong possibility you’re leaving a significant amount of money unspent.

Depending on the approach being used and your overall situation, a withdrawal rate closer to 6% or even 7% may be reasonable when the portfolio is only intended to support 20 years. This is not individualized advice, and any strategy must be evaluated in the context of your goals, risk tolerance, income sources, and overall financial picture.

The math simply changes when the time horizon changes.

Now consider an even shorter scenario. If you retire at 75 and believe your portfolio only needs to support 10 years, withdrawing just 4% per year may mean you are using less than half of what the portfolio could reasonably support. In some cases, withdrawal rates of 10% or more from the initial balance may be mathematically feasible with a shorter time horizon.

The key takeaway is this: the later you retire, the fewer years your portfolio needs to last, and the more flexibility you may have to spend. Many later retirees underspend because they apply traditional withdrawal rules to a much shorter retirement, and that can result in missed opportunities during years that matter most.

Why Optimizing the Go-Go Years Is Critical

This ties directly into the second major consideration for later retirees: making the most of the go-go years.

Retirement is often described in three phases. The go-go years are when you have the most energy, enthusiasm, and physical ability to do the things you want to do. These years are commonly thought of as roughly ages 60 to 75. The slow-go years often follow, typically between 75 and 85, when activity begins to decline. After that come the no-go years, when health and mobility can significantly limit what’s possible.

These are averages, not guarantees. Everyone’s health and circumstances are different. But the framework remains useful.

If you retire at 70, you may only have five years left in your go-go phase. Compare that to someone who retires at 62, who may have more than a decade of high-energy retirement ahead of them.

That difference matters.

When you combine this with the flexibility that often exists around spending later in life, a clear message emerges: don’t delay living. Be intentional about front-loading the experiences that matter most to you. Travel. Time with family. Giving. Purpose-driven activities.

Those go-go years do not last forever, and sometimes they end abruptly due to a health event no one anticipated. You do not get those years back.

This doesn’t mean ignoring the numbers. It means making sure the numbers support living fully while you’re best positioned to enjoy it.

Investing and Market Risk

One of the most common concerns among people who retire later is market risk. Many say, “I don’t have time to wait out a recovery.”

That concern is understandable, but it’s only part of the picture.

Even if you retire at 70, you may still have 20 or more years ahead of you. Over that time period, your portfolio needs to grow enough to keep pace with inflation and support future expenses, including potentially higher healthcare or long-term care costs.

At the same time, you do need to be intentional about how much of your portfolio is exposed to short-term market volatility.

This is where outside income sources play a critical role. People who retire later often have higher Social Security benefits because they waited to claim. If married, both spouses may have higher benefits. There may also be pensions, rental income, or other reliable cash-flow sources.

The more income you have coming from outside the portfolio, the less pressure there is on your investments to generate every dollar you need. That reduces sequence-of-returns risk, which is the risk that poor market returns early in retirement permanently damage your plan.

If the market declines and you are not forced to pull heavily from your portfolio because Social Security or other income covers core expenses, your investments have time to recover.

Retiring later does not automatically mean you should be extremely conservative. Your investment strategy should reflect your cash-flow needs, income sources, and how long your money needs to last, not just your age.

RMDs and Compressed Tax Planning Windows

Another major difference for later retirees is how close required minimum distributions are. Depending on your birth year, RMDs may begin at age 73 or 75.

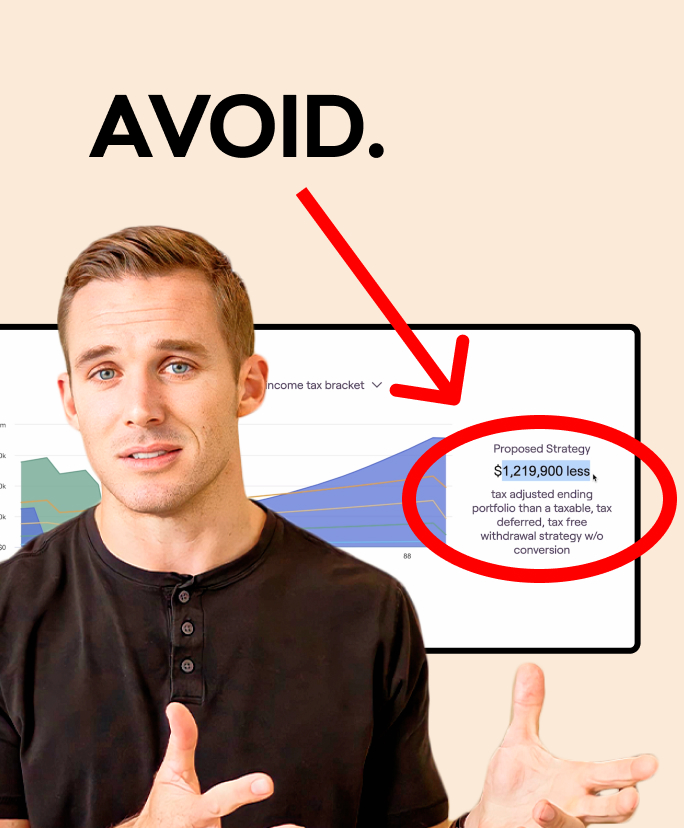

If you retire at 62 and your RMD age is 75, you may have more than a decade to implement tax strategies such as Roth conversions. If you retire at 70 and RMDs begin at 73, that window may be only three years.

The overall framework does not change, but the implementation does.

You still need to understand what tax bracket you’re in today, what bracket you’re likely to be in once RMDs begin, and how that may evolve over time. The goal is tax arbitrage: paying taxes in years when your rate is lower to avoid paying more in years when your rate is higher.

When the planning window is compressed, the margin for error shrinks. Early decisions carry more weight, and coordination across income, investments, and taxes becomes increasingly important.

Charitable Giving and QCDs

For those who are charitably inclined, qualified charitable distributions become a powerful planning tool after age 70½.

A QCD (Qualified Charitable Distribution) allows you to give directly from your IRA to a qualified charity. The amount donated is excluded from your taxable income and can count toward your required minimum distribution once RMDs begin.

This can be more tax-efficient than taking a distribution, paying taxes on it, and then gifting what remains. It also allows charities to receive the full value of the gift without tax erosion.

For many later retirees, QCDs become one of the most effective ways to align charitable goals with tax efficiency.

Medicare, IRMAA, and Income Surprises

After age 65, Medicare premiums can increase due to IRMAA surcharges, which are based on a two-year lookback at income.

If you recently retired from a high-income career, Medicare may assess higher premiums based on income that no longer reflects your reality. In some cases, you can appeal this determination by documenting a life-changing event such as retirement.

Beyond appeals, IRMAA should be treated like another tax. You should be aware of it, plan around it when appropriate, but not allow it to dictate your life choices.

Unlike ordinary income taxes, IRMAA thresholds are not progressive. Once you cross a threshold, premiums jump to the next level. If you are right on the edge, strategic planning around income sources may help avoid unnecessary costs.

Planning for the Surviving Spouse

Planning for the surviving spouse is always important, but it becomes even more critical when retiring later.

When one spouse passes away, Social Security income often decreases, tax brackets are reduced, and required distributions may remain largely unchanged. That combination can lead to significantly higher taxes for the surviving spouse if no planning has been done.

There is also an emotional and practical side to consider. Often one spouse handles the finances. Making sure both spouses understand the plan, know where assets are held, and know who to contact is essential.

Many people seek professional guidance not because they cannot manage their finances, but because they want to ensure their spouse is protected and supported if they pass first.

Health Is Not an Expense, It Is an Investment

Health deserves to be a top priority for anyone retiring later.

When you retire after 65, your go-go years are compressed. Investing in your health is not an expense; it is an investment. Without your health, even the most carefully designed financial plan loses much of its value.

Staying active, eating well, managing stress, and prioritizing physical and mental well-being directly support your ability to enjoy the retirement you worked so hard to build.

Once health declines, it is often difficult to fully regain. Prioritizing it early can make the difference between simply having a retirement plan and actually living the retirement you envisioned.

Retiring Later Is Different, Not Worse

Retiring after 65 is not a disadvantage. It is simply different.

If you intentionally design the first five to ten years of retirement, aligning spending, investments, tax strategy, and contingency planning, you can create a deeply meaningful and fulfilling retirement. But it does not happen by default.

Retirement is not just a math problem. But the math has to work so the retirement can be everything you want it to be.

The information presented is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as personalized investment or financial advice. The content discusses general retirement planning strategies and is not intended to recommend any specific course of action for any individual.

Social Security claiming strategies involve a number of variables, including life expectancy, portfolio returns, tax considerations, and personal circumstances. Decisions regarding Social Security benefits should be made in consultation with your financial advisor, taking into account your full financial picture.

Examples provided are hypothetical and for illustrative purposes only. They do not reflect any specific client situation and should not be relied upon for investment decision-making. Past performance of investments is not indicative of future results. All investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal.

Root Financial Partners, LLC provides tax planning as part of its financial planning services. However, we do not provide tax preparation services, represent clients before the IRS, or offer legal advice.

Clients should consult their CPA or attorney before implementing any tax or legal strategies discussed. Nothing in this video should be interpreted as a recommendation to take a specific tax position or legal action.

This content may include discussions around advanced financial planning strategies such as Roth conversions, backdoor Roth IRAs, tax loss harvesting, charitable giving, estate planning tactics, or Social Security claiming strategies. These concepts are general in nature and are not personalized advice. Actions related to these strategies may trigger tax consequences or legal implications. Always consult with your CPA or attorney to assess suitability based on your personal financial circumstances.

Suitability for these strategies depends on your individual tax situation, income, age, investment profile, estate plan, and other factors. Actions related to these strategies may trigger tax consequences or legal implications. Always consult with your CPA or attorney to assess suitability based on your personal financial circumstances.